Salmon live in two of the biggest oceans on Earth and the rivers flowing into them. There is only one species of salmon in the Atlantic, aptly named Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar). They are a distant relative of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) and closely related to Brown trout (Salmo trutta).

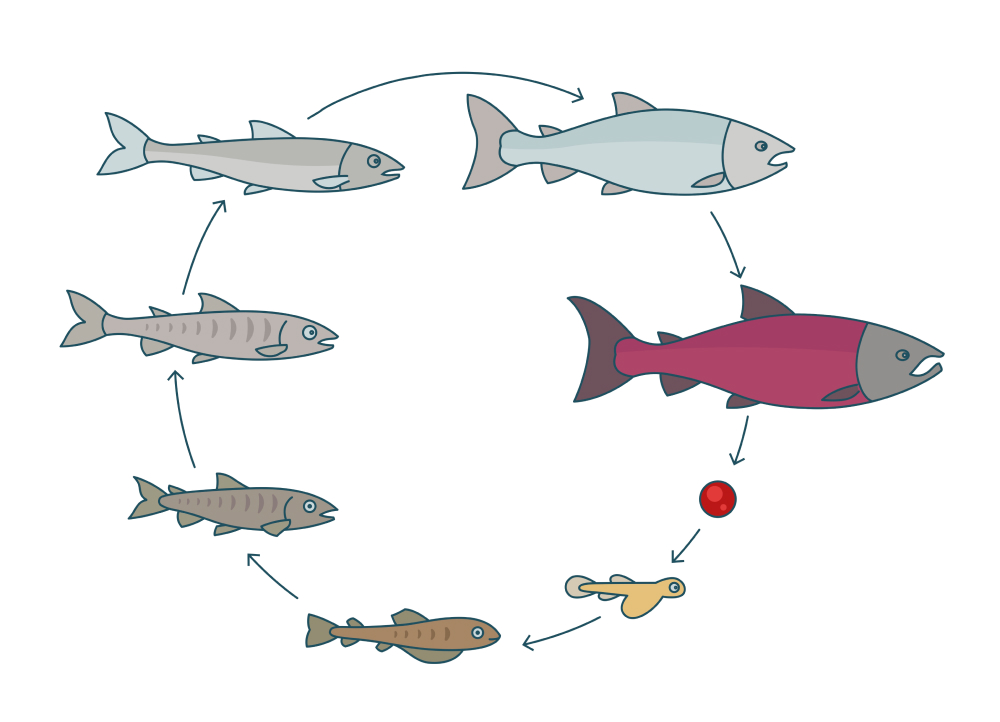

Salmon are one of the few fish species which are able to transform from living in freshwater to living in salt water. As juveniles they live in rivers, then migrate to the sea and return later to the freshwater river they were born in.

For the adult salmon, the migration from their feeding grounds in the Atlantic back to the river of their origin may start up to a year before they spawn in autumn or winter. Once in freshwater, the salmon ceases to feed to direct all their energy to swim upriver and to reproduce.

The adult female salmon dig a shallow nest in the gravel called a redd. Eggs are laid in the redd and fertilized by male fish (spawning). The female salmon buries the fertilized eggs under 12-15 cm of gravel. From now on, the salmon eggs are on their own.

Most salmon die after spawning, but those who survive will start the whole cycle again.

In early spring, the eggs will hatch after about 180 days in the gravel. The freshly hatched fish are called alevins, and still have a yolk sac attached to their bodies containing the remains of food supplied from the egg.

In early spring, the eggs will hatch after about 180 days in the gravel. The freshly hatched fish are called alevins, and still have a yolk sac attached to their bodies containing the remains of food supplied from the egg.

After a month, once most of their yolk sac is depleted, the alevins begin their journey up through the gravel.

Three to six weeks after hatching they are called fry. The small fish must rise to the surface of the water to take a gulp of air with which they fill their swim bladder. This critical period exposes the young to dangerous predators for the first time

Toward the end of their first year, young salmon develop characteristic dark bars along their side with red spots for camouflage. They are now being referred to as parr.

They feed on aquatic insects and grow for one to three years in their natal stream.

Once the parr have grown to 10–24 cm in body length, they undergo a physiological pre-adaptation to life in seawater while still in freshwater, by smolting. Smolting is the process of internal changes in the salt-regulating mechanisms of the body, and in the appearance and behaviour of the fish.

The smolts change from swimming against the current to moving with it. This adaptation prepares the smolt for its journey to the oceans.

In spring, large numbers of smolts leave Irish rivers to migrate north along the slope current into the Norwegian Sea and the greater expanse of the North Atlantic Ocean. As they grow fewer predators are able to feed on them. Their rate of growth is therefore critical to survival.

Some Irish salmon will reach maturity after one year at sea and return to their river in summertime weighing from 1 to 4 kg. If it takes two or more years to mature, the salmon will return considerably earlier in the year and larger at 3 to 15 kg – becoming a highly prized but rare fish.

Salmon exhibit a remarkable “homing instinct”, by which a very high proportion are able to locate their river of origin using the earth’s magnetic field, the “smell” of their river and pheromones released by other salmon in the river.

Having spawned, the salmon are referred to as “kelts”. Weakened by not having eaten any food since their arrival in freshwater and losing energy in a bid to reproduce successfully they are susceptible to disease and predators. Mortality after spawning can be significant, especially for males but some do survive and commence their epic journey again. In exceptional cases, some Irish salmon are known to have spawned up to three times!